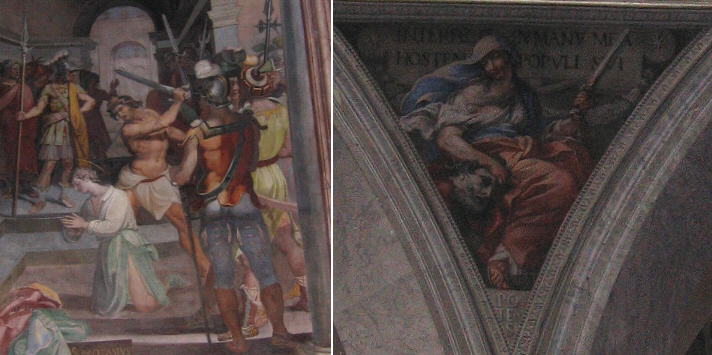

in the Churches of Rome in the Churches of Rome(the martyrdom of S. Agata (St. Agatha) - detail - in S. Agata dei Goti) Idolatry: this is one of the charges brought against the Roman Church by many Protestant leaders in the XVIth century:

the Renaissance paintings and statues which embellished the churches of Rome were seen as proof of a proclivity towards a form of idolatry, especially

because, unlike the medieval works of art, they were clearly inspired by pagan patterns of the ancient Greek and Roman world.

SS. Nereo ed Achilleo is a small church near Caracalla's Baths in a location which still retains some of the countryside appearance it had in the past. The church is not a parish and it is open almost exclusively for weddings. Notwithstanding the churchís use, the subject of the frescoes, which entirely cover its walls, could not be less in tune with the celebration of a festive ceremony. Cardinal Cesare Baronio (1538-1607) was among those who had a leading role in contrasting from a cultural viewpoint the theories of the various Protestant confessions. His Annales ecclesiastici, a history of the Church, emphasized the role of the Roman Church in the early centuries of Christianity and theorized the rightness of preserving the monuments of Ancient Rome as historical evidence of the miracles, martyrdoms and other memorable events of the first developments of the new faith. His views were accepted by the popes of his time (Gregorius XIII, Sixtus V and Clemens VIII). He defined for the 1600 Jubilee the iconographical plan of the frescoes decorating SS. Nereo ed Achilleo: the martyrdoms of some of the greatest saints of the early centuries. The design and the execution of the frescoes were entrusted to a minor painter, generally thought to be NicolÚ Circignani. The final result is that, despite the most gruesome details and the blood spilt all over the place, the neutral light and the pastel colours lead the viewer to believe he is being narrated a gentle fable, rather than a dramatic event.

S. Vitale is another minor church which was entirely decorated with frescoes at the end of the XVIth century: it was in a suburban area, while today it is entirely

surrounded by late XIXth century buildings. The late mannerism style and the light colours are very decorative, but the drama of the

scene portrayed above hits the viewer: it impacted even more the viewer of the year 1600, because, while in SS. Nereo e Achilleo the head of St. Simon perfectly sawed

into two halves raised just an anatomical curiosity, the man lying on the rack was not the nearly unknown martyr to whom S. Vitale is dedicated,

but rather (for the 1600 viewer) Giacomo Cenci,

who, having been tortured on the rack, eventually confessed the role he and his sister Beatrice had had in the killing of their brutal father. The

individual viewing this fresco in 1600 would also be reminded of the philosopher Giordano Bruno

accused of heresy, who did not abjure his opinions and was burnt alive in Campo de' Fiori. The details of the rack show that the painter was well aware of its mechanisms, because in that period it

was routinely used by the Roman prosecutors, in particular by those of Tribunale del Sant'Uffizio (o Inquisizione).

Even when the prosecutors had gathered enough evidence to substantiate the charge, they made use of the rack to obtain

a full confession: in this way they thought they had helped the culprit by saving his soul, a very noble aim indeed.

Sadism: form of sexual perversion marked by love of cruelty; deriving of pleasure from inflicting or watching cruelty.

The works of art portraying tortures inflicted on some heroines of Christianity lend weight

to the suspicion that sadism existed well before Marquis de Sade gave his name to it. In his Voyage en Italie he described how he enjoyed

the sight of some works of art decorating the Roman churches: in particular

the statue of S. Cecilia.

Charles Dickens wrote a very interesting account of a beheading he saw in Rome in 1845. It was the usual way executions were carried out and in general they attracted a lot of people. So the Romans were accustomed to seeing heads rolling into a basket and then executioners holding them by the hair and showing them to the people. It is not unusual to see paintings and sculptures showing beheadings and not only with reference to the martyrdoms of saints.

In 1571 the Turks, breaking the terms signed to obtain the surrender of Famagosta, flayed alive Marcantonio Bragadin, the Venetian commander of the fortress. This event, rather than the martyrdom of St. Bartholomew, is what the 1600 viewer saw in this gruesome painting in SS. Nereo ed Achilleo (note the character, portrayed on the left in the fresco wearing a Turkish turban). St. John came out unscathed from the cauldron of boiling oil shown in the fresco, and peacefully ended his days in exile on the island of Patmos.

Dickens described the paintings he saw in S. Stefano Rotondo as a panorama of horror and butchery, a sort of catalogue of all the conceivable means to torture and put to death a human being: the fresco shown above combines two different capital punishments: lapidation, which is usually associated with punishment of adulterers, and burying alive, the melodramatic fate of Aida and Radames.

Mannerist painters portrayed the most bloody and horrific martyrdoms in such a formal and decorative way, that, notwithstanding the subject, their paintings looked "nice". It was the task of a great painter to show the dramatic end of the first saints. Caravaggio did not indulge in gruesome details, but his use of light and his not idealized bodies conveyed a pathos which eventually led some of those who had commissioned him a painting, to refuse it because of its being too real. Caravaggio had many followers and soon no painter could disregard the use of light he had introduced: at this point the recommended iconography for portraying saints was adjusted to the new way of painting: the martyrdoms were no longer shown as they occurred, but through something which reminded people of the way the martyrs had been put to death, or, as in the examples here below, in a phase preceding the actual event: so Guido Reni showed St. Michael while he just threatens the Evil and St. Lawrence was portrayed while he was being pushed towards the almost hidden grill, rather than while actually suffering on it.

The image shown as background for this page portrays the Flagellation of S. Gervasio in S. Vitale.

See also my List of Baroque Architects and my Directory of Baroque Sculpture. Go to my Home

Page on Baroque Rome or to my Home Page on Rome

in the footsteps of an XVIIIth century traveller.

|

All images © 1999 - 2005 by Roberto Piperno. Write to romapip@quipo.it